Artifical pancreas systems

in: Health and Well-Being

The NIH, in tandem with private and public universities, pushed the development and testing of artificial pancreas systems, which help people with type I diabetes automatically monitor and fix their blood sugar levels.

About 1.45 million people in the United States have type I diabetes, a disease that renders the pancreas unable to regulate blood sugar. The pancreas normally regulates blood sugar using two hormones, one of which is insulin. Insulin helps take sugar out of the blood and into muscle or other tissues. People suffering from type I diabetes need to carefully monitor their blood sugar levels. If they see their blood sugar get too high, they should self-administer some insulin. But how much insulin? Getting the amount right can be very tricky. Too high a dose of insulin leads to hypoglycemia (which is a fancy name for too low blood sugar), too low a dose of insulin and the high blood sugar level issue has not been solved. Getting the dose wrong can lead to further health complications.

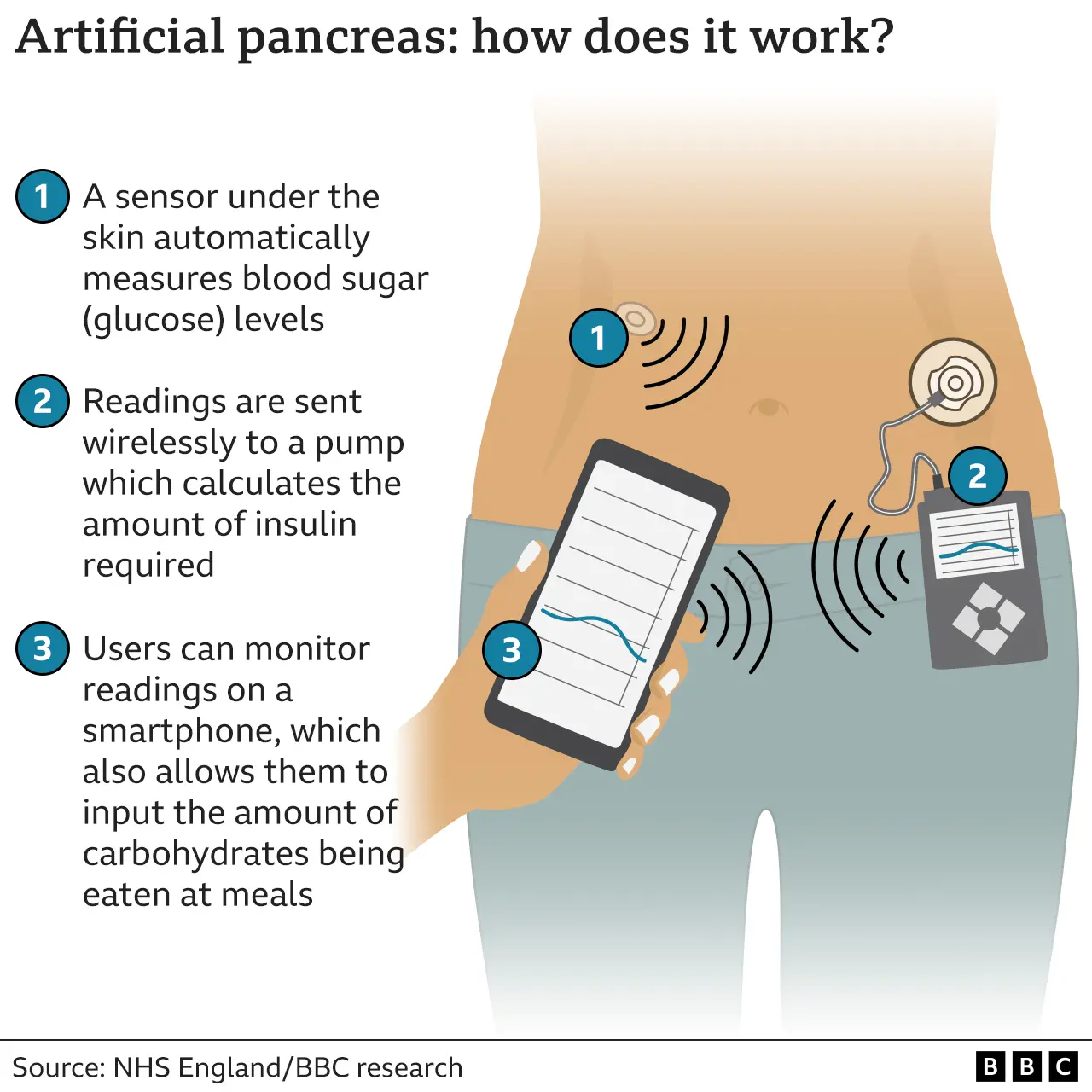

In order to better control blood sugar, the NIH and universities across the United States worked together to develop artificial pancreas systems. These devices essentially try to do the pancreas’ job for it. They break the problem down into 3 components: first, monitoring how much glucose is in the blood; second, using the level read from the monitor to calculate the correct dose of insulin that should be given; and third, administering the insulin. Each of these problems is solved by one device, and the combination of all 3 is known as an artificial pancreas. Glucose monitoring is done via a tiny sensor that is placed underneath the skin, usually via some adhesive pad. A program on a smartphone or some other physical device then gets information from the sensor and uses it to calculate the proper dosage of insulin necessary to keep blood sugar at a desired level. Lastly, insulin is delivered via a tiny pump that goes underneath the skin.

These systems were developed by a collaboration between the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDKK) and universities in the Boston area, namely Harvard Medical School and Boston University. This effort included not only prototyping and development, but also extensive clinical trials to ensure safety for young children. These systems have made it easier for people to monitor their blood sugar throughout the night and, in particular have made life much easier for young children and the elderly dealing with type I diabetes. It’s great for the doctors, too: the doctors get much more detailed information about the status of their patients than they used to, which allows them to better tailor treatment to each individual patient.

- States: MA , MD

- Organizations: National Institutes of Health , Harvard University , Boston University

- Topics: Biology , Health

- Links and further reading: [ link1 | link2 | link3 | link4 | link5 ]